In this interview with RUDOLF INDERST, Nicolas Deneschau, author of ›The Last of Us: Auf der Suche nach Menschlichkeit,‹ unpacks the series‘ polarizing yet powerful storytelling. Deneschau highlights how Naughty Dog’s design choice of „constraint“ forces players to commit acts they might find detestable, pushing them to reflect deeply on the characters‘ humanity. He discusses the creative risks that marked Naughty Dog’s shift to grim realism, influenced by post-9/11 »post-apocalyptic fiction« and inspirations like Cormac McCarthy’s ›No Country for Old Men‹. Discover how Deneschau believes ›The Last of Us‹ transformed video games from vehicles of »fun« into powerful conduits for »emotion«, permanently raising the bar for narrative in the medium by prioritizing memorable, even if divisive, endings.

Rudolf Inderst: It’s a great pleasure to talk to Nicolas Deneschau today. Nicolas, could you please introduce yourself to our readers?

Nicolas Deneschau: First of all, thank you for this request. I am a journalist specializing in video games for several French magazines (Jeux Vidéo Magazine, Metal Hurlant, etc.) and I am particularly interested in video game storytelling. I have already had the opportunity to write a handful of books that address these issues for Uncharted, Monkey Island, or Alone in the Dark, for example. I am one of those people who are convinced that the video game medium offers prodigious tools to immerse us in stories in a new way.

Nicolas, The Last of Us is often praised for its storytelling, but it also polarizes players with morally ambiguous moments, I am thinking of Joel’s hospital choice, Ellie’s pursuit of revenge. How do you think the series, across games and TV, balances visceral emotional punches with deeper questions about humanity?

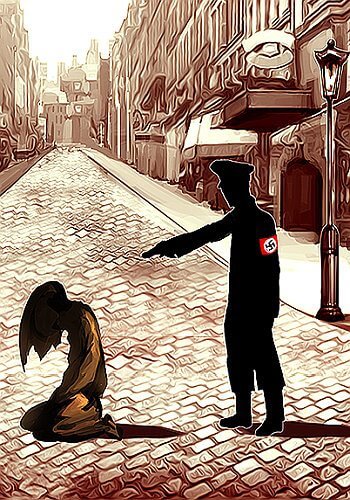

I think there are many possible answers to this question. In fact, it’s a question that permeates my book throughout the chapters. Nevertheless, there’s an interesting element in some of Naughty Dog’s game design choices, notably that of constraint. Video games, the art of interactivity par excellence, have long explored the possibility of interacting with events by offering choices. For example, do I choose to sacrifice this character for the good of humanity? Or do I prefer to save him? Yes / No. End of story. Here, on the contrary, the design forces us to make certain character choices, but to suffer the consequences in a very direct way. In both games, we’re regularly forced to commit acts that we might consider detestable or, at the very least, far removed from our true nature. I think this is also one of the reasons why The Last of Us, and Part II in particular, appeals so strongly to gamers‘ sensibilities. The effectiveness of such a process, in my opinion, is that it forces us to reflect on the consequences of these actions (in which we actively participate, joystick in hand, in a very visceral way) and, consequently, to question the humanity of the various characters. Had the design been different, the story would have stuck to our expectations, and the player would have no opportunity to question anything.

I think there are many possible answers to this question. In fact, it’s a question that permeates my book throughout the chapters. Nevertheless, there’s an interesting element in some of Naughty Dog’s game design choices, notably that of constraint. Video games, the art of interactivity par excellence, have long explored the possibility of interacting with events by offering choices. For example, do I choose to sacrifice this character for the good of humanity? Or do I prefer to save him? Yes / No. End of story. Here, on the contrary, the design forces us to make certain character choices, but to suffer the consequences in a very direct way. In both games, we’re regularly forced to commit acts that we might consider detestable or, at the very least, far removed from our true nature. I think this is also one of the reasons why The Last of Us, and Part II in particular, appeals so strongly to gamers‘ sensibilities. The effectiveness of such a process, in my opinion, is that it forces us to reflect on the consequences of these actions (in which we actively participate, joystick in hand, in a very visceral way) and, consequently, to question the humanity of the various characters. Had the design been different, the story would have stuck to our expectations, and the player would have no opportunity to question anything.

It’s a bit like the anti-RPG. The game seems to make every effort not to conform to the player’s expectations. The TV series also seems to me to make similar choices. And, inevitably, these decisions raise questions and leave no one indifferent. Let’s not forget that one of Neil Druckmann and Bruce Straley’s mantras was »do we prefer to make an ending that pleases everyone but that everyone will have forgotten? Or an ending that 50% of people will hate, but that we’ll still be talking about years later?«

Your book traces Naughty Dog’s shift from Uncharted’s swashbuckling adventures to TLOU’s grim realism. What creative risks defined this transition? Were there internal struggles that reshaped their vision?

The first shift took place in the early 2000s. On the initiative of Allan Becker and Shuhei Yoshida, Sony undertook a »conquest of Hollywood« by attempting a rapprochement with the American dream factory. In concrete terms, this meant betting heavily on studios such as Santa Monica (God of War) and Naughty Dog. The idea is to blur the boundaries between big-budget games and summer blockbusters.

This marriage gave birth to great game series such as God of War and Uncharted. The second shift is as much a creative impulse as it is an opportune context. On the one hand, post-apocalyptic games, zombies, etc. were all the rage in the 2010s, with the great popularity of series such as Walking Dead, and on the other, ›The Last of Us‹ fits completely into a global creative context in Hollywood that could be called »post-apocalyptic fiction post-9/11«. A fictional sub-genre that imagines America after its collapse. After the attacks, innumerable series, comics, films etc. began to erupt around the question of a devastated America. More or less consciously, Neil Druckmann has fully integrated himself into this vein. The cartoon-pulp aspect perhaps no longer really corresponded to the social and political aspirations of this new generation of creators.

You highlight Cormac McCarthy’s influence, The Road’s bleakness is often cited, but are there subtler inspirations (films, books, even music) that shaped TLOU’s world?

Oh, the inspirations are endless. Some are conscious, others unconscious. But among the main ones, beyond The Road of course, I’d cite ›No Country for Old Men‹, the Coen brothers‘ film (Joel is named Joel after one of the two Coen brothers). The film really set the tone for both games, this very realistic, very raw side to the violence. For its influence on character development, David Bennioff’s novel ›City of Thieves‹ was a determining factor. But, of course, we can add the film I am Legend for its artistic direction, the inevitable Walking Dead etc…

Part II forces players into uncomfortable violence like Abby’s fight against Ellie. Do you think the gameplay mechanics enhanced the narrative’s moral weight, or risked alienating players?

Well, I’ve already answered most of that question. I’m absolutely convinced that it’s a decisive ludic mechanism that totally underlines the narrative. I think the effect is twofold. Indeed, the aim is to make players feel the weight of their actions and, inevitably, some will find this detestable. But, like every narrative work in every medium, the aim is to make the player feel something, and not necessarily something positive. Here, video games are not a vehicle for fun, but for emotion.

With the HBO show’s success and Part II’s divisiveness, do you think TLOU has permanently raised the bar for storytelling in games? Where should the medium go next? Could you name other games with the same impact?

On a personal level, I’m convinced that The Last of Us, the first, in 2010, pushed back a milestone in particular in the integration of a quality standard in acting, in something more subtle in video game staging. Now, with the TV series, I think that milestone has been erased. Because the universe and quality standards of today’s TV series are exceptional, and the historical milestones are not the same. TLOU is a video game that made its mark, while the TLOU series is a more commonplace series in today’s television field. For video games, however, there is still an incredible universe of possibilities in terms of narrative tools. Return of the Obra Dinn, Outer Wilds and Blue Prince spring to mind. But the possibilities seem endless, to our great delight. Nevertheless, what the TV series reflects is that these are two very distinct mediums. One is not better than the other, they just have different tools at their disposal to bring these stories to life.

In my last question for today, I’d like to zoom out a bit. What’s your general impression today of the field of game studies and research?

I’m not well placed to talk about Game Studies. My work is not part of a rigorous scientific process, but rather a matter of commentary and observation, and I don’t see it as fitting into this more academic framework. Nevertheless, beyond the fact that it’s extremely pleasant and exciting to see a young medium being taken seriously, I’ve noticed above all that since the emergence of Game Studies, we’ve seen the arrival of new generations of creators, whether in independent games or AAA, who reflect new ways of approaching video games. It’s as if we’re witnessing the progression of cinema at an accelerated pace, and it’s impossible to predict its future.

Thank you, Nicolas, for these insights! The Last of Us – Auf der Suche nach Menschlichkeit is available now from Look Behind You.

Titelangaben

Nicolas Deneschau: The Last of Us – Auf der Suche nach Menschlichkeit

Übersetzt von Franz Kubaczyk

Rheinbreitbach: Look Behind You 2025

368 Seiten, 29,90 Euro

| Erwerben Sie dieses Buch portofrei bei Osiander

Reinschauen

| Leseprobe

| Link zum Spieletrailer #1 (YouTube)

| Link zum Spieletrailer #2 (YouTube)

| Link zum Serien-Trailer (YouTube)