What happens when a non-gamer history teacher and a Belarusian game developer meet by chance in Gothenburg? Out of their long conversations about education grew The Great Gambit—a classroom-ready strategy game that challenges students not to “guess the past,” but to live through its dilemmas. In this interview with RUDOLF THOMAS INDERST, the duo explains how cooperative prevention, social maturity, and historical complexity became the heart of their design.

Rudolf Thomas Inderst (RTI): Let’s start at the beginning. Could you each introduce yourselves and tell us a bit about your background? What was the personal spark for each of you—the historian and the game designer—that led you to join forces and create The Great Gambit?

ZL (Zhenya Luchaninau): I’m originally from Belarus and have been working in the game development industry for six years. My academic background is in architecture, but ever since my student days I’ve been fascinated by the idea of combining games and education. I tried creating different projects, but each time I ran into obstacles that, at that stage, felt impossible to overcome. When I came to Sweden to work, I became curious to learn more about their school system, which is often described as progressive.

ZL (Zhenya Luchaninau): I’m originally from Belarus and have been working in the game development industry for six years. My academic background is in architecture, but ever since my student days I’ve been fascinated by the idea of combining games and education. I tried creating different projects, but each time I ran into obstacles that, at that stage, felt impossible to overcome. When I came to Sweden to work, I became curious to learn more about their school system, which is often described as progressive.

And then, one evening in September 2022, I met Anders completely by chance— in a small park in central Gothenburg, around a bonfire where two people were cooking pasta. As we got to know each other, I discovered that one of them was a history teacher. I asked if we could meet again so he could tell me more about Swedish education from the inside. That was the beginning of our year-and-a-half-long conversation about schools and learning. At some point I said: “Why don’t we build a game project together?” and Anders agreed to join the adventure. I had tried to launch educational projects before, but only this time everything finally aligned—the opportunity, the people, the technology, the experience.

AK (Anders Kjellberg): I’ve been teaching history and Swedish for about 14 years now and in my free time, I’m a musician. When Zhenya first asked me to talk about the Swedish school system, I thought: “It’s not every day a Belarusian shows up wanting to discuss things like this!” and I was intrigued. For many months we exchanged ideas and reflections about education.

AK (Anders Kjellberg): I’ve been teaching history and Swedish for about 14 years now and in my free time, I’m a musician. When Zhenya first asked me to talk about the Swedish school system, I thought: “It’s not every day a Belarusian shows up wanting to discuss things like this!” and I was intrigued. For many months we exchanged ideas and reflections about education.

When Zhenya suggested creating a game, I saw it as a real challenge for myself as a teacher. To be honest, at first I was worried—I had never played games, and here I was about to help make one. But Zhenya told me he was actually glad I wasn’t a gamer, because it meant we could design something that even teachers with no gaming experience would still be able to use and understand.

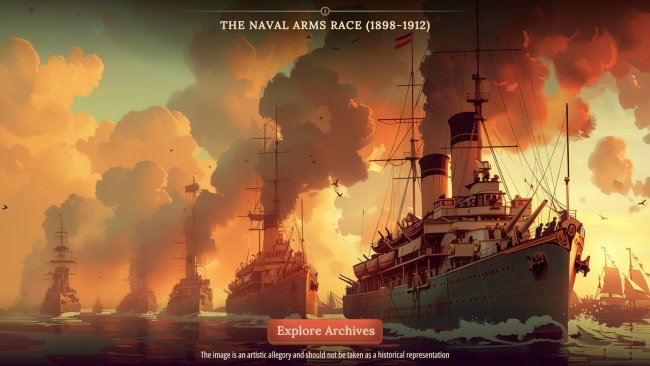

The period we are covering in the game is, in my opinion, one that hasn’t been as well documented as the wars they led up to. I think giving the students a solid backstory about the late 19th century might help them to understand the chaotic 20th century, which is a period in time that for young people today might seem as far away as the 1700s. Another thing that sparked me is the obvious similarity between our uncertain times and the time leading up to the First World War. If the students can make those comparisons themselves after a play session, I know the game is a hit!

RTI: Your project emphasizes that the goal is not to find the „right“ historical choice but to experience the underlying social dynamics. Can you elaborate on why this shift from finding answers to living with complexity is so crucial for teaching history, and how „social maturity“ manifests during a game session?

ZL: I think when history is taught as a search for the “right answer,” two distortions inevitably appear: hindsight bias (“of course, they should have done X”) and moral self-assurance (“I would have chosen better”). In The Great Gambit we deliberately shift the focus from not “guess the past,” but “live through the constraints.”

Why is this crucial for history? Because historical actors operated under norms, incentives, and fears that tend to vanish in a textbook. Reading about Workers, Civilians, Political Leaders, and Colonial Administrators of that time is one thing, but living through their dilemmas is something entirely different. In the game, students feel the weight of limited options and conflicting pressures that shaped those historical actors.

As for social maturity, we understand it not as a personality trait or a level of intelligence, but as a practice of collective thinking. It’s the ability to hold contradictions, to see the system from multiple perspectives, to recognize the logic of others even when it’s uncomfortable. In the game this becomes visible: students stop speaking in terms of “they” and begin saying “we,” they try to anticipate others’ actions, and they discuss not only “what benefits us” but also “what keeps the space open for everyone.”

In those moments, students start to sense how difficult it is to sustain the stability of a system. And it is precisely this feeling—that your choice is always woven into a larger fabric of relationships—that we call the manifestation of social maturity.

AK: Social maturity is a really good expression! Young people of today are intelligent, but they need knowledge to activate their intelligence. Being intelligent includes having an ability to see patterns and to connect phenomena with each other, and playing a game where you’re forced into another person’s shoes requires dedication. Just finding the right answer by memorizing dates or names gives little use of the history subject in your day-to-day life, while “living” the past and studying the longer lines of history is, in my opinion, a better way to use your intelligence and might also work as a method to use historical knowledge in a practical way. (Hope I interpreted your question right here!)

RTI: Designing a game where the objective is to prevent an event we know historically happened is a fascinating challenge. What were the key mechanics you had to implement to make „cooperative prevention“ a tense, engaging, and achievable goal for the students, rather than a foregone conclusion?

ZL: For me, designing mechanics where the objective is to prevent an event that we know did, in fact, happen was perhaps one of the most difficult challenges. I couldn’t just take an existing mechanic from another game and adapt it because that would have felt superficial. Instead, I took a different path: I immersed myself in the period, read research in history, psychology, and international relations, and analyzed primary sources. My goal was to design mechanics that, even in simplified form, would reflect the realities of that time.

This was especially important when it came to the victory condition. We designed it as a kind of hypothesis: what would have needed to happen to avoid catastrophe? There is still no definitive answer to that question, but that doesn’t mean it cannot be discussed. The game creates precisely that kind of space for reflection, for debate, even for deconstruction. Students and teachers can challenge the mechanics, asking: could it be done differently? or is it really fair to assume the condition should be set this way?

The core victory mechanic is built on two parallel conditions: a collective one—preserving peace, and a personal one—becoming the group with the greatest influence. Which goal to pursue is entirely up to the students; no one forces their choice.

The collective condition works like this: peace is only possible if every group reaches at least 35 gems. Why? Because a “low-level balance,” say, 10–12–11–10 gems across the four groups, may look fair internally, but it is not enough for the country to be taken seriously on the international stage.

It’s important to stress that influence (gems) in our model is not about raw power or strength, but about the ability to be heard:

– within the country: as the voice of a social group,

– internationally: as the voice of the nation itself.

Reaching 35 doesn’t mean “beating history”; it means creating conditions where society still has room to choose a different path.

The concept for this mechanic came from studying the international dynamics of 1871–1914. Looking at the crises of that era, we can see that most “solutions” only narrowed the range of alternatives rather than resolving the underlying problems that caused the crises in the first place. In the game, students pass through a similar chain of crises, and the central question becomes: can they preserve space for maneuver, or will they step by step cement the trajectory toward escalation?

What makes this engaging and tense? I think the constant collision between collective and personal goals. The challenge is sharpened by hidden modifiers (role alignment, ethical trade-offs), group psychology, rare but risky gambits, and the consolidation mechanic, which rewards not superficial agreement but a real attempt to understand the logic of others. All of this makes “cooperative prevention” not a given, but an achievable and fragile goal.

AK: I think one difficult challenge was to place yourself in those times when giving the decision cards the moral points. We obviously see the world through 21st-century eyes and have a morality based on our upbringing in the modern world. Today, for example, flooding a village—which is on one decision card—would be an outrageous act, but seen through the eyes of a European in the late 19th century, that action would probably seem acceptable.

We wanted to give the game a realistic touch by working quite hard with the moral aspect. As a history teacher, that is always hard: I really try to make them understand that we can’t judge actions in the past from our world view, but we must learn about those actions so we don’t repeat them.

RTI: You’ve mentioned very encouraging feedback from Swedish schools and have already translated the game into German. What has been the most surprising or insightful reaction from either a teacher or a student, and how does that feedback shape the future development and international expansion of The Great Gambit?

ZL: There was one moment that really surprised me in a positive way. I spoke with a teacher who had used our game in his classroom and asked him: “So, were our tutorial videos on how to play clear to you?” He looked at me and said: “Tutorial? Why would we need that? We decided to figure it out ourselves with the students—and we did.”

There was also a moment with the students. I watched a session where the Workers group absolutely refused to cooperate. They kept saying: “It feels like nobody cares about us, so why should we engage in dialogue?” Then, on the fifth turn, the Political Leaders chose a decision card that gave a direct benefit to the Workers. Suddenly the Workers said: “Okay, now we’re ready to talk about cooperation.” It was fun to watch them inhabit their roles so vividly. But there were opposite situations too: once, a group of Political Leaders declared they would “play as proper politicians” and only make the “right” decisions. Very quickly, they drove the situation into a dead end and actually accelerated the path to catastrophe.

Now, about how feedback shapes the development and expansion of the project. In truth, the impact is enormous. For example, one teacher’s comment led us to completely rewrite all the decision cards and even redesign the objectives of the entire Civilians group. Another piece of feedback helped us cut the instructions from five pages down to two. That shows how important feedback is to us—it really changes the game.

But there’s another level as well. Feedback from different countries helped us sharpen the very idea of the project. At first glance, it might seem like a game only about Germany before World War I, so maybe it’s relevant only for German schools. But in fact, it’s quite the opposite. The real theme of our game is not “German history” as such, but the interaction of groups and the psychology behind it. And that’s universal.

Our mechanics allow us to discuss important questions in many different contexts: pre-war Germany, the Soviet Union during the Cold War, Ancient Egypt, and more. The key point is that any society is built on groups constantly interacting. Whether you take a corporation with its departments or a social movement with its internal factions, the same principle applies everywhere.

And it’s this universality that gives us confidence the project can expand internationally. Because what we’re showing is not just one specific storyline, but the deeper fabric of how societies work.

AK: Knowing my students and how they usually behave in the classroom, it struck me that some of them, who are usually quiet and a bit shy, took command and got engaged in a way I hadn’t seen before.

Also, the direct reaction from the students gives so much energy and encouragement for me in my role as a teacher. One of them asked if he could take the beta version home to play it… as a pre-party activity on their graduation day! Quite fun to get that kind of response! A less direct response but just as valuable is seeing their examination results. This year I spotted a difference in how deeply they could analyze the road to war and use that period to understand our times.

A challenge was to make the gameplay flow and to use the time between sessions wisely; you don’t wanna move too fast or dwell too long in the descriptions about the events.

Other than that, I agree with Zhenya; getting direct feedback from my colleagues was really valuable and unlocked parts of the game that caused obstacles for the experience as a whole—for example, the Civilians mentioned above.

The future of the game? Well, I think just using it in more subjects than history would be interesting. Maybe trying it out in a psychology class as a conversation starter about group psychology? It might also work in the Swedish subject and maybe also in German or English class.

RTI: Let’s zoom out a little at the end: How do you assess the current state of game studies, and what structural challenges do you think the field faces?

ZL: What I see right now in the field of educational games is an imbalance: most of these products are created by academics and teachers themselves. That’s good in one sense, such games are often very strong from a methodological perspective. But the downside is that they are rarely truly engaging for students. More often they feel like “a digital textbook with buttons.” Bringing people from the game industry into this space is incredibly difficult. There isn’t the same money here as in commercial game development, and the field itself is still only beginning to take shape.

Yes, there are commercial educational games, but they are usually designed for personal use at home, as a kind of “learn while you play” in your free time. My area of interest is different—universities and schools. I want to create tools that actually work in the classroom, together with teachers and students. And it might sound like you could just bring in specialists from the game industry and everything would be fine. But the task of combining genuine engagement with real educational value in one product is, by itself, a huge challenge.

On the other hand, I see clear demand. Teachers in universities and schools are genuinely interested in such tools. And I think the reason is simple: new generations of educators themselves grew up with games. They don’t need to be convinced that “games can teach,” they feel it intuitively. That’s why I believe demand will only continue to grow, and with it will come new formats and new teams capable of combining the expertise of teachers with the expertise of developers.

RTI: Thank you very much for talking to us, and good luck with this exciting project!

FURTHER INFO

| Official website

| The Great Gambit Community Facebook Group

| Support Page – Buy Me a Coffee