Menschen | Interview: Daniel Berehulak (Teil I)

Daniel Berehulak ist einer der meistdekorierten Foto-Journalisten unserer Zeit. Er berichtet aus über 60 Ländern – über Kriege im Irak und in Afghanistan, den Prozess gegen Saddam Hussein, Kinderarbeit in Indien, das Leben nach dem Tsunami in Japan und aus Manila. FLORIAN STURM sprach mit ihm über die rigorose Anti-Drogen-Politik des philippinischen Präsidenten Rodrigo Duterte.

Daniel, the president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, started his term about 118 months ago. His policy on drugs has been criticised strongly all over the world. Has anything changed regarding his anti-drug-war since your story came out about one year ago?

Daniel Berehulak: Colleagues in the Philippines told me, that there was a response from the president’s office saying the story was completely one-sided. All the main-stream media also picked it up and spread the news on it.

The Philippine journalists have been covering the issue from the very start in July last year but over time, the general public lost interest. So, my photo series put the issue back on the public agenda.

Earlier this morning, a woman who went out with the nightcrawlers – that’s what the journalists call the team going out during the night – told me via e-mail that the killings still continue, though. Now however, there are less so called »police operations«, but more vigilante killings. That’s the reason why it’s hard to say whether things have actually changed because a lot of murders are being categorised as crimes (only). When the police are collecting and putting together the data, they do it in a way which makes it more difficult to attribute it to the anti-drug-war.

Did you receive a special treatment from the Philippine police because you were a foreign journalist?

No, because I worked very closely with the local journalists. Most of the time, I worked with Rica Concepcion, my fixer and translator, who has almost 30 years of experience in the region.

The story was and still is so big that journalists from various agencies and newspapers are sharing information. We all see the urgent need to report on it in order to eventually see these killings stop. By sharing information, we are more effective than had we worked completely on our own.

Who actually connects you to these fixers?

Usually, I have to track them down myself. However, over the years, I’ve built a vast network of journalists, friends and colleagues all over the world that I can reach out to. It’s a mutual relationship that works both ways, of course. We all try to help each other out.

Has this story been your toughest assignment so far?

It was extremely challenging and certainly ranks amongst the toughest and most gruelling ones – for several reasons: We (Rica, our driver and I) had to be out there as much as possible – to report, to come across these important scenes and to follow up with families.

We mainly worked during the night but often had to work during the day as well. There was hardly any pause because something was happening nearly all the time. That means we weren’t bound by the hours of the day or any patterns at all. Anything could happen at any time.

Apart from that, seeing death day in, day out was of course incredibly difficult.

Does one somehow get used to this?

No, not at all. In my career, I have also covered various stories in Pakistan, from military offensives to suicide bombings from the Taliban. There was a time in Islamabad when I thought I was getting desensitized to the horror of it, but I have learned by now that all of it catches up with you eventually – be it that you’re depressed for a week or more or that you get nightmares. It still affects me differently every time. Sometime it gets me on the spot, sometimes it’ll be an hour, a week or even a year later.

How did you cope in the Philippines?

You need to make sure to get some rest, that you’re eating well and that you process things in one way or another. Nevertheless, halfway through I started getting nightmares and I was seeing things because I was delirious sometimes. However, this responsibility deep inside keeps you going nevertheless.

Have you developed strategies that help you cope with what you’ve experienced?

I talk a lot with friends and colleagues, take time off after an assignment to completely clear my mind or even totally immerse myself in the emotion and let everything out. There are different methods that work on different occasions.

You have visited more than 41 crime scenes documenting 57 homicides, interviewed dozens of witnesses and family members of the victims. Is there any situation that stands out from the others?

Yes, Jimji, a six-years-old girl, mourning the death of her father Jimboy Bolasa (25). They were taking the casket away from the wake on the way to the funeral. When they were leaving Jimji ran up to the coffin so one family member had to hold her back while she screamed her father’s name. She simply didn’t want to leave his side. I still remember seeing her raw anguish and pain. This summed up the pain everyone in the community experienced. It’s a scene I’ll never forget.

You were in the Philippines for 35 days. Was that a fixed duration from the beginning?

No, neither me nor my editor, David Furst from the New York Times, knew how long it would last. This also meant every day could’ve been my last with David calling me and sending me to another story that had just broken. With this uncertainty, there always came this sense of urgency. I felt the responsibility to work as much and as hard as I possibly could.

What were your days like?

There were no normal days, but I’d usually meet the other guys at the media office near one of the police’s district headquarters offices around 9 pm.

But isn’t the police part of the problem as they are trying to cover up any drug-related murders?

The media office is on the premises of the police, but not in the same building which allowed us to work quite independently from the police themselves – certainly not with them.

They were tolerating our presence, but weren’t all us assisting us in any way. Quite the contrary, in fact. Unless somebody from our team had already established a relationship with a certain guy at the police – who then secretly tipped us off – they didn’t share information and tried to keep the media from reporting on it. Not openly, but in a very subtle way.

What would that look like?

When the journalist started covering the issue, they simply followed the police as they left the premises in order to get to the crime scenes. When the police eventually realised what was going on and, they got a lot sneakier with cars being dispatched from somewhere else or going via the back entrance.

In addition to that, they tried to control the crime scenes and kept the photographers at a further distance than previously. Or bodies were taken away more quickly so that there wouldn’t be a crime scene in the first place. These corpses would then pop up in random places that were unrelated to any drug-related-incident.

Let’s go back to what your days were like…

After starting around 9 in the evening, some days I’d get back to the hotel at 5 or even 8 in the morning. Sometimes, we even worked for 36 hours straight. You basically try to get sleep wherever you can, be it in the hotel or in the back of a car whilst driving to another appointment.

On some occasions, I came home early in the morning after a shift, slept for a few hours and then Rica called telling me of a police operation which we need to go to immediately or that the jail finally gave us access.

Did you have the chance – physically and mentally – to take a break?

No, not really. But as I was there for a limited period of time only, I didn’t want to take a rest. Despite from that, it’s different when there’s nothing happening. When I was there, we had on average 24 killings a day. If we weren’t reporting on it, these people wouldn’t get their stories told.

Most killings happened late in the evening or at night. With those happening during the day, there was no way in the world you’d get anywhere near the crime with the dense Manila traffic before it was completely shut down by the police.

During the day, when things were quieter, Rica and me would do our own reporting – conduct interviews, trail follow-up-leads, attend funerals, follow families to morgues, spend time in communities.

How difficult was it to get access to those people? After all, mourning is a very private issue in most cultures.

It is a very private thing there, too. But keep in mind that if you are in a country where the judicial system has completely broken down, journalists are often the only opportunity for families to share their side of the story and the impact it’s having on them.

When you speak to the family, they tell you a completely different story of what happened: that they just had dinner or were leaving a party when masked people entered their house and dragged their son, father or husband away; that these men cold-bloodedly murdered their loved ones; that there had been no resistance; that the victims wouldn’t own a gun, hadn’t done drugs in months or have in fact never been associated with drugs at all.

Most of these killings are copy-paste-murders where things have obviously been set-up: the same revolver placed perfectly next to the hands of the victim, a little bag of methamphetamines in their top-pocket – always the top-pocket – of the body lying upwards. Each crime scene nearly looked identical.

These people are operating in complete and utter impunity and are allowed to use lethal force if the person is fighting back. They are the law. All of the cases I covered in which the police were involved, the victims weren’t arrested or even wounded [as they would when fighting back] – they were shot dead. End of story.

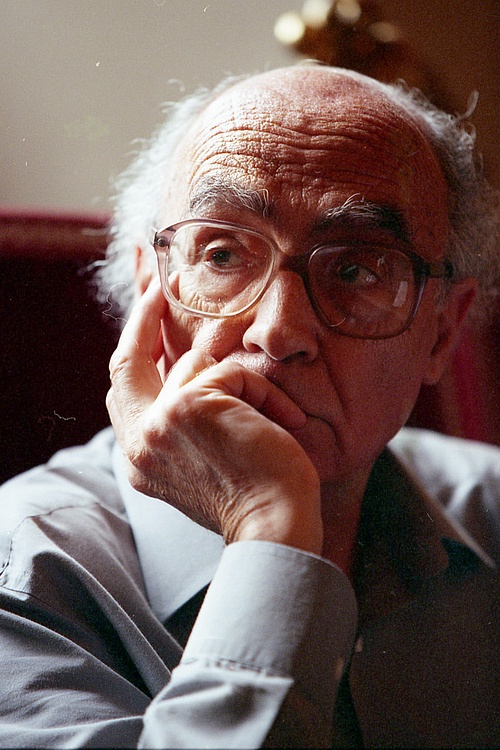

Über Daniel Berehulak

Daniel Berehulak was born in Sydney, Australia, in 1975 as a son of Ukrainian immigrants. He studied history at the University of New South Wales and initially wanted to become an entrepreneur. In 2000, he picked up photography and started working for a sports agency. Two years later, he had his first assignment with Getty Images Sydney, in 2005 he was sent to work in their office in London. By now, Daniel works as a freelance journalist, in the recent past mainly for the New York Times. He has been reporting from over 60 countries – about wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the trial against Saddam Hussein, child labor in India, the life after the tsunami in Japan and of course from Manila. Daniel has received numerous awards for his photographs, included the World Press Photo Award (5x) and the Pulitzer Prize (2).

Weiterlesen

| Webseite von Daniel Berehulak

| Die vollständige multimediale Berichterstattung über den Drogenkrieg in Manila (›They Are Slaughtering Us Like Animals‹), die Daniel Berehulak für die New York Times gemacht hat, und die mit dem Pulitzer-Preis ausgezeichnet wurde, lesen Sie hier.